kayla jessop

Fatherhood in 15 Words

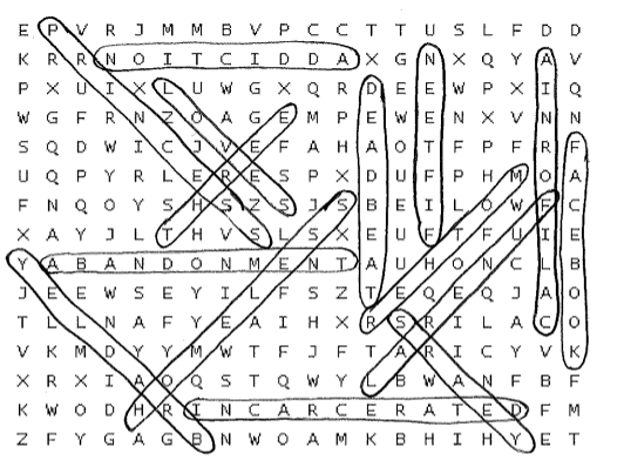

Word List

Bradley

Fifteen

Three

Abandonment

Princess

Deadbeat

Mother

Addiction

Years

California

Homeless

Loves

Incarcerated

Facebook

Funeral

Your name was Bradley. You preferred “Brad,” but you’d answer to whichever. Your mother wanted a girl, but by the time you arrived, wrapped in a small, blue blanket, she didn’t know what to name you. She let her mother and sister decide on your name. A common boy’s name in 1982.

You became a father at fifteen. It was a shock to both you and your girlfriend, but only sort of. You never used protection, and she wasn’t on birth control. Adoption never crossed either of your minds because you were excited about the positive test. You knew, instinctively, that your mother would help. You had the neighbor tell her about the pregnancy because you were too scared of her reaction. Your mother is kind, too kind, but you’d been a disappointment in your early teen years: experimenting with drugs, stealing money and/or televisions from the house, dropping out of the eighth grade, and being a nuisance to all her neighbors.

You have three children, all daughters. Two from the same woman, one from the first woman you dated after the breakup with the first mother. You were closer to the oldest, not because you loved her more than the others, but because she’s the most stubborn and took on the most responsibility, never wanting her sisters to feel the weight of having you as their father.

Since her young age, you’d given her: a handful of toys she’d long outgrown, a mirror for her room that you drew flowers on in a Sharpie, and an abundance of abandonment issues. You passed this on through generations: your father from his abusive father, you from your absent father, and then her from you being absent most of the time, visiting her at her mother’s house when it was convenient and you were sober enough—from alcohol or drugs—to be present.

You have called her “princess” since the Halloween when she went as Cinderella for the second year in a row. You ghosted her the first year because you took your newest daughter trick or treating. Or maybe you were partying, you don’t remember. “She sat on the front stoop waiting for you,” her mother told you once. “She didn’t trick or treat at all.” The second year, you were so late that by the time you got there, she was already out of her costume, sprawled out in the living room with her sister counting their candy. You didn’t come to any other Halloweens after that.

Her mother introduced her to a new word when she was seven. She asked you what “deadbeat'' meant on a phone call. It was the first phone call you had with her and her sister for months. When you asked her where she heard it from, she said her mother told her that’s what you were. She didn’t elaborate any more than that, too young to remember why her mother said that. But still, you took your anger out on her, even though she didn’t understand what it meant. She cried for her mother, sobbing that you were yelling at her. Her mother hung up the phone without saying a word to you. You didn’t call again for months, maybe even a year.

By the time you did call again, you found out that she was living with your mother and not her own. It wasn’t a shock: deep down, everyone knew she would end up there. It always felt like you two had the same mother, the way yours took care of her so diligently since she was born: buying her clothes, taking her to and from school, scheduling her doctor’s appointments. She was the daughter your mother didn’t get to have. You were surprised to hear about her mother, though: in and out of jail, struggling with her own addictions. You knew she had the habit but didn’t know she was back on it at the time. You thanked your mother for being so good to her. You told her you loved her and missed her. She told you that she was taking her out of Maryland. “Building a house,” she told you. She offered for you to come, too, when you were ready to be on track. But you weren’t ready, knowing that “on track” meant rehab and sobriety, so you told her you would see her when she visits home in Maryland.

Two years after their move, you joined her and your mother in South Carolina after a string of bad luck and stern lectures from your mother about your behavior. It was the first time you lived with your daughter since before she was five. At nine, she was able to play catch, go hiking, and carry on conversations with you. She was nothing at all like you and her mother were: she was, and still is, sensitive, soft spoken, constantly worried about everything from the change of your tone to whether you would be there to pick her up from school like you said you would. She didn't like to be alone, worried each time you left the house. You thought it was annoying. “Childish,” you told her once when she cried when you wouldn’t take her out the door with you. Your mother pulled you aside and told you that you needed to be more patient with her. “She’s a kid. She’s used to you being in and out,” she told you during what became an argument. But you didn’t stop being in and out of her life. The years you spent in South Carolina with her are the first time she saw your addiction. She rode along with your mother when she had to pick you up from jail; she changed your clothes for you when you snuck into the house, too drunk or too high to do so yourself. When your mother questioned her about it, she told your mother that she didn’t, that she was asleep by the time you came in. You told her the next morning, as you always did, that it’s wrong to lie, but you brought her ice cream after school. The first time you went to rehab in South Carolina and came back, she asked you questions about where you had been. You and your mother told her “the doctor,” but she was eleven then and must have known better. You hoped not, though.

After you left South Carolina on a random Thursday after a fight with your step-father and mother, it was six years before anyone heard from you again, and it wasn’t even you that contacted them. Your girlfriend found your daughter on Facebook. She messaged her to tell her that you missed her and your mother. She told your daughter that you didn't know that she contacted her. It was the truth. And by the time you conjured up the nerves to call them, weeks after the initial contact, you learned that she was in college, a rising senior at nineteen, younger than her classmates. She always was smart, so you weren’t surprised. She told you all about her college experience, her future career plans, and her day in and day out routine of working to help pay bills and finding time to study between that. You realized then that you missed out on all the big moments: her first date, her first heartbreak, her high school graduation, and cheering her on when her college acceptance came. You knew that you would also miss out on the future moments, too. She knew it, too, probably more than you did.

In California, you spent your days skateboarding and exploring different parts of San Rafael. You got there by hitchhiking with your girlfriend: sticking your thumb up as you walked down the interstate, like in a movie. Some people drove you state to state, others only to the nearest city. They were rarely kind-hearted people, but you didn’t expect that from a stranger willing to pick up another stranger. They always wanted something: money, drugs, or worse. You were used to it. After all, you were one in the same. Eventually, you found a crowd of people like you—lost, looking for an escape from the reality you had created. In doing so, you created a new family, one where there weren’t any judgments or responsibilities.

You were homeless, but you didn’t mind it. You actually preferred it. You could move around the city as you pleased. Occasionally, your stuff got stolen or confiscated by the police for loitering, but you didn’t mind that either. It was a chance for you to start over. You lived in a tent made of cascading blankets and sticks. Occasionally, it was an actual tent, but those were harder to steal or they got stolen from other homeless people. The space was always small, but you liked to hear the crickets and frogs at night. You always liked the wilderness. The best part of it was the food. Because of the richness of the city, the homeless shelters fed you well: steaks, potatoes, soups, and more. You went with your friends, other homeless people you met out there. The worst, or maybe the real best part, was that your friends were like you: drug addicts. There was never not an opportunity to score. You spent the majority of your days high, skateboarding, and stealing items from local shops. On days you did get caught, you spent the next few weeks in jail, only to get out and repeat your usual cycle.

Your daughter reminded you that she loves you every time you talked. Usually, because your communication skills weren’t great or because you were too busy with your lack of responsibilities, you only talked every six months or so. The conversations were usually short. You told her what you had been up to without ever sugar coating anything: stints in jail—though she already knew, constantly checking sites to see if you were still alive—you told her about the drugs you’d been doing, the fights you’d been in. You talked eagerly about the conspiracy theories you were into. You asked her for money, and though she wanted to lecture you each time, she never did and always agreed to send it. When she tried to talk about deeper things like her usual offer for you to come home, get clean, see your children and mother, you would tell her that you had to go, had something else to do. She reminded you to call her soon, to be safe, and keep her phone number in your pocket. “I love you too, princess,” you would tell her.

The last time you talked to her was while you were incarcerated. She called the jail, knowing you were there from the bookings log, to tell you that her mother had died. You cried with her on the phone. “She’s the only woman I ever loved,” you told her. “I always thought we would get back together.” But you hadn’t been together since you were seventeen, and you hadn’t talked to her in upwards of ten years. Still, you cried. You didn’t ask your daughter how she was doing or offer her any support. You didn’t ask about what she planned to do for the funeral, how her sister was doing, nothing. Instead, you asked her to send you money for your commissary account. She promised you that she would send it. You promised to call her. She sent the money a few days later. You never did call her.

After not hearing from you for six months, she took to Facebook to try to find you. She posted on your wall, hoping your friends would relay the message that she was worried and looking for you. She tagged all of your Facebooks—the four of them you made over the years because you could never remember your passwords—in a post asking if anyone had seen or heard from you. A few of them had, they wrote to her. A few said they were sorry for her. She messaged your girlfriend repeatedly, begging her to put you on the phone so she could hear your voice. She never did.

Two weeks after a new missing persons post, the police called her. It was a random Sunday in November of 2020, three weeks before her 23rd birthday. She was painting a bedroom in your mother’s new house when she answered the call from an unknown California number with the news that you had died. The police told her that it looked like an overdose, but they wouldn’t know for certain until they did an autopsy. For the next few days, she planned her second funeral for a parent that year, except there was no funeral for you. Coronavirus cases were too high for your mother and her to travel to collect you and your few belongings: a skateboard, an out-of-fluid lighter, a pocket knife, and more random things that were in your wallet. They had you cremated, sent home to them in South Carolina in a priority mail box. They cried as the two of them placed your ashes in a blue, moon-lit water designed urn. Your mother picked it out on Amazon. It reminded her of you because you loved the water. Now, you sit on the shelf of your mother’s china cabinet, touched by soft fingers each time they walk by you and being lightly dusted on occasion. You turned thirty-nine years old on that shelf, forever in place, home with your mother.

kayla jessop

Kayla Jessop is an MFA candidate at Lindenwood University. Her nonfiction has been published in Tempo, Harpur Palate, Broad River Review, You Might Need To Hear This, Lindenwood Review, Variant Literature, Welter, and Press Pause Press. She does her best writing while sitting in coffee shops and daydreaming about possibilities. In her free time, when she’s not teaching, she enjoys cross-stitching and watching New Girl.